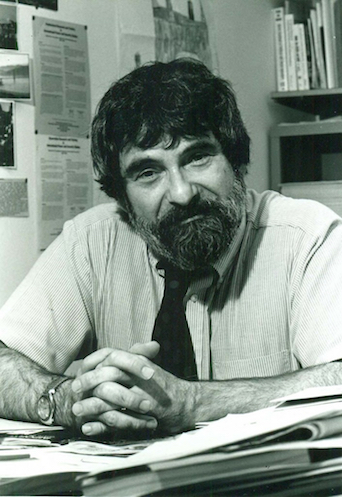

Dennis J.D. Sandole

Dennis and I, of course, go back a very long way – almost five decades to be more precise, back to the late 1960’s. At the time we were both graduate students in Britain. I was working for John Burton at the old Centre for the Analysis of Conflict at University College in London; Dennis was up in Glasgow at Strathclyde University – one of the “Strathclyde mafia”, a cohort of bright political scientists – Peter Willetts, Mick Marsh, Keith Webb, Dennis and others - who would all go on to be influential professors in their own right, and to modernize political studies in Britain into a social science rather than a branch of history.

At the time, Strathclyde was one of the few university departments in the country that took numbers and measurement seriously. One of the results of this was that Dennis was grappling with a dissertation that combined complex simulation studies with a massive data analysis problem and it was taking an age to complete – in my memory, more than a decade. But Dennis beavered away and finally produced his doctorate. He persisted and this – to me - illustrates one of Dennis’ chief characteristics as an individual; sheer persistence, stickability and obstinate determination. Later, it also struck me that his struggles with his own dissertation helped to explain why he was so sympathetic to the doctoral students he helped to supervise and mentor towards their own doctorates. He knew from experience how difficult it was to complete a doctoral degree.

The Strathclyde connection hardly helped Dennis with John Burton’s team when he applied for a teaching job at UCL. John neither believed in numbers nor approved of quantification. Dennis often described his depressed train journey back to Glasgow after having been grilled at University College. He had had a disastrous interview. Nobody was interested in the work he was doing. He had blown his chances of a job. So, he was surprised a week later to receive a letter offering him a post at UCL to teach, among other subjects, methodology. Obviously, the UCL interviewers had seen something fundamentally worthwhile other than his ability to count and compute.

That began Dennis’ sojourn in London, teaching at UCL, a period which lasted from – I think – 1971 until 1975, when the international relations program there fell victim to the first of many subsequent rounds of government cuts in British university funding and the transfer of the CAC’s remnants down to the University of Kent. Dennis was un-tenured so he didn’t make the move and ended up putting together some teaching here, some supervision there. The good old days were not such a golden era of job availability as some students today might imagine. Mainly, Dennis stayed employed by working for the overseas International Relations program that the University of Southern California ran for the U.S army in southern Germany. I was working on a similar program run for the U.S. Air Force based in eastern England, so we stayed colleagues. This meant a weekly commute from London to Frankfort and back, which did not leave much time for research or writing - or the completing of dissertations. On the other hand, it was from this era that one of his former students made a comment that stuck with me as summarizing another of Dennis’ typical teaching qualities. The student – a colonel in the U.S. army – told me that “Taking a class from Dr. Sandole is rather like trying to take a drink from a fire hydrant!” I knew what he meant.

Moreover, Dennis also managed to stay an active member of the group of former CAC scholars – described by one of its members as an “invisible college” - that met regularly to discuss ideas, theories and drafts of books and articles - and survived for almost 20 years. He worked with others on a handbook of conflict resolution that was intended to replace “Getting to Yes” as a best seller in the canon. But it never saw the light of day.

Then, after five years of patching together a career in the increasingly bleak academic landscape of the UK, Dennis decided to return home and became part of a new, experimental program in conflict analysis at George Mason University. The Center for Conflict Resolution was the brain child of Bryant Wedge and some of his colleagues arising from the unsuccessful 1970’s campaign to realize Thomas Jefferson’s original idea for a U.S. Department of Peace, intended to match and supplement the work of the Department of State. The Center was, fortunately, an interesting innovation in the eyes of then GMU President George Johnson so CCR started its history with a Faculty Advisory Board (which included a young anthropology professor called Kevin Avruch), a half time Director, a half time Deputy Director, a half time executive secretary and half of a full-time faculty member. This last was Dennis, who, for a time, was shared between CCR and the Department of Politics and International Relations.

So Dennis was the first ever formal teaching appointment to the new Center, and for the next five years he, Bryant Wedge, Henry Barringer, and Mary Lynn Boland carried the CCR – later to be the CCAR, ICAR and finally S-CAR – from survival - just - as a small master’s program, to expansion as the first PhD in the country and eventually to a fully-fledged and prestigious university teaching program in “Conflict Analysis and Resolution.”

But we should make no mistake about it. The experiment started initially in 1981 could very well have failed, and the fact that it did not is owed very much to that early quartet of appointments and to their dedication to the Center and especially to Dennis’ continuing commitment and determination over nearly 40 years of service as a teacher, a mentor, an author, and a researcher. He was my colleague at GMU for almost 30 years; We worked together in Northern Ireland and in the Caucasus, where I re-acquainted myself with Dennis’s qualities of dedication, humour, persistence and unflappability – as well as his ability to ignore well meaning advice if he thought it was nonsense.

Above all, I came to appreciate his ability to rebound after setbacks and not to give up when things did not quite go according to plan. Of course, this quality was much needed during the last ten years of his illness, and was central to the long battle he and Ingrid waged together against his illness, the side effects of the many treatments, and the horrors of the U.S. health care system. He carried on teaching and writing right up until his last relapse just over a year ago, and when I offered occasionally to take a couple of classes for him, he always thanked me courteously and said he would let me know. He never did.

In the end, he lost this last battle, as we all must. He leaves behind a huge gap in the field, in the School and the University, in the lives of his family and friends. But he also leaves behind the example of a life gallantly lived and persistently – and against all odds - dedicated to making the world a better place.

Left to right: Ron Fisher, Kevin Avruch, Chris Mitchell, Dean Pruitt, Dennis Sandole.