S-CAR’s newest faculty member sees lessons for modern-day conflict resolution in the history of racial violence and early Civil Rights activism in the United States.

Dr. Charles L. Chavis, Jr. (second from right) attended a March 14, 2019, community dialogue organized by S-CAR students Tanja Thompson, Bethany Holland, Jordan Mrvos, and Audrey Williams (from left to right). (Photo credit: Charles Chavis)

By Audrey Williams

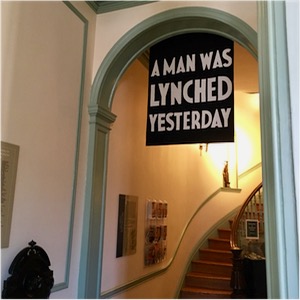

At 1320 Eutaw Place in Baltimore, a red-brick townhouse sits along a wide, tree-lined street, welcoming visitors in through its teal front door. Once the home of Civil Rights leader Dr. Lillie Carroll Jackson, the house is now a museum honoring both her and her family’s efforts to combat early-20th-century segregation and racial violence in Maryland and across the United States.

As soon as visitors walk through that teal door, they are confronted with the injustice and terror that Dr. Jackson and her community fought against.

Hanging in the foyer is a black flag bearing the chilling words “A MAN WAS LYNCHED YESTERDAY.” The flag is a replica of the one that the NAACP would hang outside of its New York headquarters to bear witness to the victims of lynching in the United States.

A replica of a flag that the NAACP would hang at its New York City headquarters hangs in the Lillie Carroll Jackson Civil Rights Museum in Baltimore, MD. (Photo credit: Audrey Williams)

For Dr. Charles Chavis—a historian of the Early Civil Rights Movement who has served as both a fellow and a program coordinator at the Lillie Carroll Jackson Civil Rights Museum (LCJM)—this jarring experience of being confronted with the racial violence of lynching has raised questions of how museums can serve as sites not only of education but also of racial healing and reconciliation.

It’s a subject he will explore as the newest faculty member at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University, where, as an assistant professor, he will bring his training in historiography and archival methods to bear on the field of conflict resolution and peace studies.

A commitment to salvaging marginalized histories

When the S-CAR search committee set about the task of recruiting the school’s newest faculty member, the committee’s chair, Dr. Solon Simmons, made sure to “include an appeal to historians.”

“We've always placed a lot of value on history,” he said. “A lot of us do work that brings history in, or that's quasi-historical, but we never, as far as I understand, have had a historian on the faculty.”

As the school’s first historian, Chavis is poised to do the kind of research, teaching, and practice that not only shows “the importance of the study of history for peacebuilding,” according to Simmons, but also “solidifies why it is we have such difficulty in the United States still, and why it goes back to the Civil War and race relations.

With his dissertation research on the last lynching in Maryland—which will become a book titled ‘Maryland, My Maryland’: The Murder of Matthew Williams and the Politics of Racism in the Free State—Chavis has endeavored to broaden the understanding of the history of lynching in the United States.

During his job talk at S-CAR last fall, he said that much of the work being done on the history of racial violence focuses on lynchings in the Deep South. With his research on the lynching of Matthew Williams, who was murdered in 1931 in Salisbury, Maryland, he wanted to draw attention to the history of racial violence in other parts of the country.

He also wanted to go beyond tracking the scale of the violence. “A lot of [the literature] focuses on the abstractions of statistics, and I wanted to focus on the human story,” he said. To that end, the first chapter of his book “focuses on salvaging the story of Matthew Williams, his family, his community, and his humanity.”

Chavis calls himself a “salvaging expert,” committed to uncovering the often difficult-to-find stories of the African American community in the United States. His formal training in archival methods, on which he relied during his dissertation research, is key to this endeavor.

“When you’re dealing with the history of marginalized communities, you have to have a level of, as my grandmother would say, ‘stick-to-it-ness,’” he said during his job talk. “[W]hen we look at the ways in which archives are structured, they’re not structured in a way that takes into consideration the stories of those who are marginalized.”

Simmons noted that Chavis’s training in archival research is particularly useful for the study of conflict resolution.

“You need people who are historically aware, or [else] you can't reconstruct the way in which violence is lived in everyday experience today,” he said.

Of the 271 candidates who applied for the assistant professor position, Simmons said that the committee—which included Dr. Pamina Firchow, Dr. Karina Korostelina, Dr. Susan Allen, and Dr. Terrence Lyons—was “unified in its support for [Chavis] really throughout the entire process.”

“I think that everyone could see immediately why you'd want to have this capacity to re-tell and re-imagine these difficult stories of racial violence, and how important it is to move forward in the human process,” he said.

A commitment to transformative practice

Whereas academic debates continue around scholars’ engagement in practice alongside research, at S-CAR, a commitment to both is a prerequisite. The advertisement for the assistant professor position was explicit in its search for “candidates who engage directly with today’s real-world conflicts through intervention, advocacy, public scholarship, consultation, action research, evaluation and other forms of practice.”

As a historian coming from a “traditionalist department,” S-CAR’s commitment to both theory and practice was very attractive to Chavis.

“I've always believed that the work that I do should have some type of meaning and should bring about change if possible,” he said. “[W]hat I really think is important is that S-CAR values you as your individual discipline, so I am a […] historian, but I'm a historian who also does conflict resolution.”

“Dr. Chavis’s work strengthens S-CAR’s commitment to research and practice on race, violence, and the Civil Rights Movement,” said Dr. Kevin Avruch, Dean of the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. “As a public historian, working in museums and other forums, Dr. Chavis brings a different dimension and sensibility to larger American narratives of deep-rooted conflicts around race and identity.

Chavis’s public practice has included projects funded by the National Park Service, including an “intergenerational oral history project” that “connect[ed] inner-city Baltimore youth with Civil Rights pioneers from the Baltimore Civil Rights Movement,” he told S-CAR News.

The project allowed inner-city youth to interview pioneers in Baltimore who had worked with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackie Robinson, and others. Not only did the project broaden understanding around the “lived narratives of these local pioneers,” it also had a “conflict resolution piece” in that it helped the students “find personal meaning” in these narratives.

“The majority of these students live in the inner city of Baltimore, and their relationship with their local history is a problematic one,” Chavis said. During his job talk, he discussed the project in the context of the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in April 2015.

“As we watched youth come into [the LCJM...] constantly we saw students struggle with issues dealing with how this history is connected to what they’re living and what they’re experiencing,” Chavis said. Specifically, he noted that students discussed the question of whether Freddie Gray was lynched.

Dr. Charles L. Chavis, Jr. was a speaker on a February 26, 2019, panel on "Race and Society in Nazi Germany and the US: From Swastika to Jim Crow." The event was organized by the United State Holocaust Memorial Museum and the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. (Photo credit: Charles Chavis)

A commitment to reconciliation

It's important to Chavis his work to draw links between the legacy of lynching and police brutality today.

In the present day, many museums—such as the Equal Justice Initiative's [EJI] Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama—also trace the history of lynching and slavery to their modern-day legacies, such as mass incarceration and police brutality. Chavis is adamant that the efforts of such museums need to go beyond education.

“[T]he work of these institutions demonstrates [that] there is a need to correct the existing narrative associated [with] the history of racial violence in the United States,” Chavis told S-CAR News. However, “these institutions fail to move beyond truth-telling or ‘narrative change,’ and as a result, visitors are oftentimes left to process this traumatic history without a mechanism for moving towards racial healing and reconciliation.”

At S-CAR, Chavis is hoping to get students involved in research, fieldwork, and practice that uncovers the role that museums, monuments, and memorials can play in “facilitate[ing] racial reconciliation as well as social transformation” in the United States.

He aims to begin a project around “historical monuments and community remembrance” that will “promote memorials as places of reconciliation” and will “help develop urban and municipal memorials to victims of racial violence throughout the community and state.” He is looking forward to incorporating fieldwork at museums in the D.C. and Baltimore area into his classes.

Chavis will be teaching Conflict and Race (CONF 721) during the Fall 2019 semester, but some students in Dr. Sara Cobb’s Spring 2019 Facilitation Skills (CONF 657) course got an early taste of Chavis’s commitment to student education.

On March 14, 2019, Chavis attended a World Café dialogue that S-CAR students Tanja Thompson, Jordan Mrvos, Bethany Holland, and Audrey Williams organized in Leesburg around memorials set to recognize the victims of lynchings in Loudoun County.

Speaking from his experience as a museum professional interested in creating spaces for healing and reconciliation, Chavis called the March 14 dialogue “groundbreaking.”

“In employing the World Café method, S-CAR students were able to aid the community in establishing connections across siloes, in turn, filling in the gap [and] successfully moving the community of Leesburg, VA, from truth-telling and closer to racial healing,” he told S-CAR News.

The S-CAR students were honored to have him participate.

“His support for S-CAR students before his first semester shows how dedicated he is to accompanying students through the learning process,” said Holland, who added that his participation in the World Café dialogue—a method meant to encourage the creation of collective intelligence among dialogue participants—“really exemplif[ied] his passion and dedication to continuing and honoring discussions around race, history, and preservation.”

Starting in August, the broader S-CAR community will also have the opportunity to experience Chavis’s dedication and passion firsthand. Anticipation around his work is palpable at the school.

“Already you start to notice people around campus are picking up on his work and are interested in what he does,” said Simmons.

Thompson, who hopes to take Chavis’s classes, is excited to learn how “he views race from a historical perspective and the role it plays in today’s society,” adding that she is especially eager to “hear more about his work with EJI and how other communities can engage in holistic dialogue around lynching.”

The excitement goes both ways.

“I can't wait to start […] doing the work of justice at S-CAR,” Chavis told S-CAR News. “It's really an honor to be a part of this new community, and I look forward to working with the students and the faculty. I think I'm just as excited as everyone else.”

Biography

Charles L. Chavis, Jr. is Assistant Professor of Conflict Analysis and Resolution and History and Director of the Program for Racial Reconciliation, Justice, and Historical Memory in America at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University. Before joining the S-CAR, he served as the Museum Coordinator for the Lillie Carroll Jackson Civil Rights Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr. Chavis is a historian and museum educator whose work focuses on the history of racial violence and civil rights activism and Black and Jewish relations in the American South, and the ways in which the historical understandings of racial violence and Civil Rights activism can inform current and future approaches to peacebuilding and conflict resolution throughout the world. His areas of specialization include Civil Rights oral history, historical consciousness, and racial violence and reconciliation. He has received over twenty-five grants, awards, and fellowships from organizations including the Robert M. Bell Center for Civil Rights in Education, Knapp Family Foundation, American Jewish Archives, The National Museum of African American History and Culture, National Trust for Historic Preservation, National Park Service, and the American Historical Association.

Professor Chavis has published more than twenty-five refereed articles, reference articles, essays, reviews, op-editorials, chapters, and government reports, and is author of the upcoming book ‘Maryland, My Maryland’: The Lynching of Matthew Williams and the Politics of Racism in the Free State and editor of For the Sake of Peace: Africana Perspectives on Racism, Justice, and Peace in America (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

He received his PhD in History from Morgan State University (2018), his M.T.S. in Black Church Studies from Vanderbilt University (2014), and his B.A. in African American Studies from the University of North Carolina Greensboro (2012).