From September 4 to September 17, 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter worked closely with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to broker peace between their two countries.

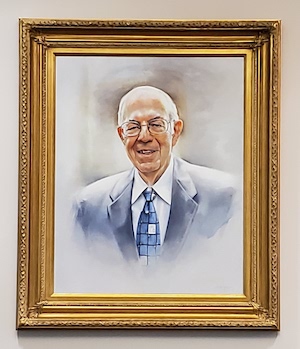

A late member of the Carter School community, Harold “Hal” Saunders, played a pivotal role as representatives of the three countries worked toward peace.

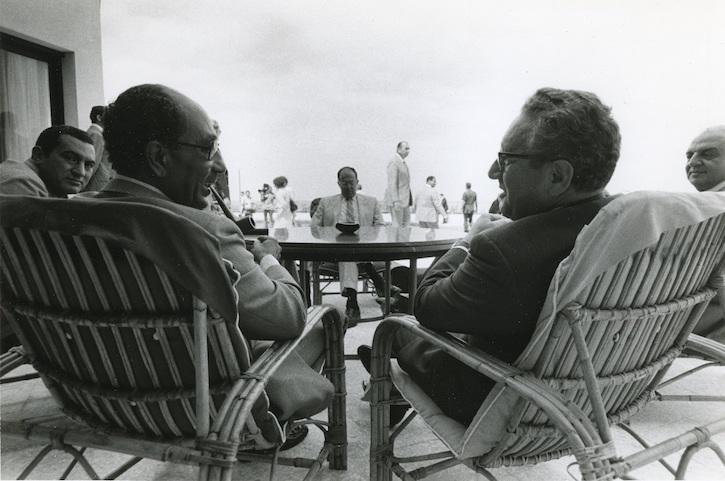

Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat (left) and U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (right) speak together as part of the U.S.'s shuttle diplomacy efforts. At the far end of the table sits Harold “Hal” Saunders, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs.

By Audrey Williams

Cathy Saunders, the daughter of Harold “Hal” Saunders, was a teenager at the time her father, then a State Department official, was helping U.S. President Jimmy Carter to facilitate one of the most defining peace negotiations of the 20th century: the Camp David Accords.

The talks, carried out over thirteen days in September of 1978 by President Carter, Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, along with their teams of advisors, would enable the governments of Egypt and Israel to sign a peace treaty in March of 1979.

It hasn’t been violated since.

Cathy is now a professor of composition and literature at George Mason University, where her father taught at what was then the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution and is now the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

She told Carter School News that the accords impressed upon her the vital role that interpersonal relationships play in peacemaking, especially in situations with global political impact.

She said that the success of the accords depended on “the fact that they all went away—a relatively small group of people, including some very powerful people—and talked to each other directly and deeply, and got to know each other as people.”

At the time, Cathy’s father Hal was the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs. Prior to his assumption of the role in 1978, he had spent the better part of the ‘70s flying back and forth between Washington and the Middle East as part of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s “shuttle diplomacy,” which the U.S. was carrying out between Israel and its neighbors.

For Hal, it was the salvaging of the personal in the political that drove his interest in peace and conflict resolution.

“That kind of person-to-person [contact] and really getting to know people as people was very important to him,” Cathy reflected.

At Camp David, it was a fraught personal relationship between Begin and Sadat that nearly derailed the entire peace process—and a personal touch by President Carter that saw it through.

Supporting peace between Israel and its neighbors was a priority for Jimmy Carter when he became the President of the United States in 1977.

“I made repeated promises that I would seek to invigorate the dormant peace effort,” President Carter reflected in his 2006 book, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid.

Between January 1977 and September 1978, President Carter and his State Department worked closely with Sadat, Begin, and their teams to find a way to bring Egypt and Israel to the negotiating table.

It quickly became clear to President Carter that just as the relationship between Egypt and Israel was burdened with distrust and doubt, so too was the relationship between Sadat and Begin.

In private, separate meetings with both leaders, President Carter could see that each was willing to consider a discussion on the major issues between their two countries, which had fought multiple wars since the creation of Israel in 1948.

Those issues included “Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories, Palestinian rights, Israel’s security, an end to the Arab trade embargo, open borders between Israel and Egypt, the rights of Israeli ships to transit the Suez Canal, and the sensitive issues concerning sovereignty over Jerusalem and access to holy places,” President Carter wrote in 2006.

After months of promising discussions followed by periods of renewed frustration between both leaders, President Carter invited Sadat and Begin to Camp David to negotiate in the beauty and isolation of the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland.

The act was “almost one of desperation,” President Carter reflected in 2006, but Sadat and Begin immediately agreed to join him.

Stuart Eizenstat, who served as the White House Domestic Affairs Advisor to President Carter, spoke about the Camp David Accords during an October 2018 discussion organized by the Carter School around Eizentstat’s book, President Carter: The White House Years.

In advance of the talks, President Carter “pored over intelligence records on Prime Minister Begin of Israel and President Anwar Sadat of Egypt to understand their character, to understand their red lines,” said Eizenstat.

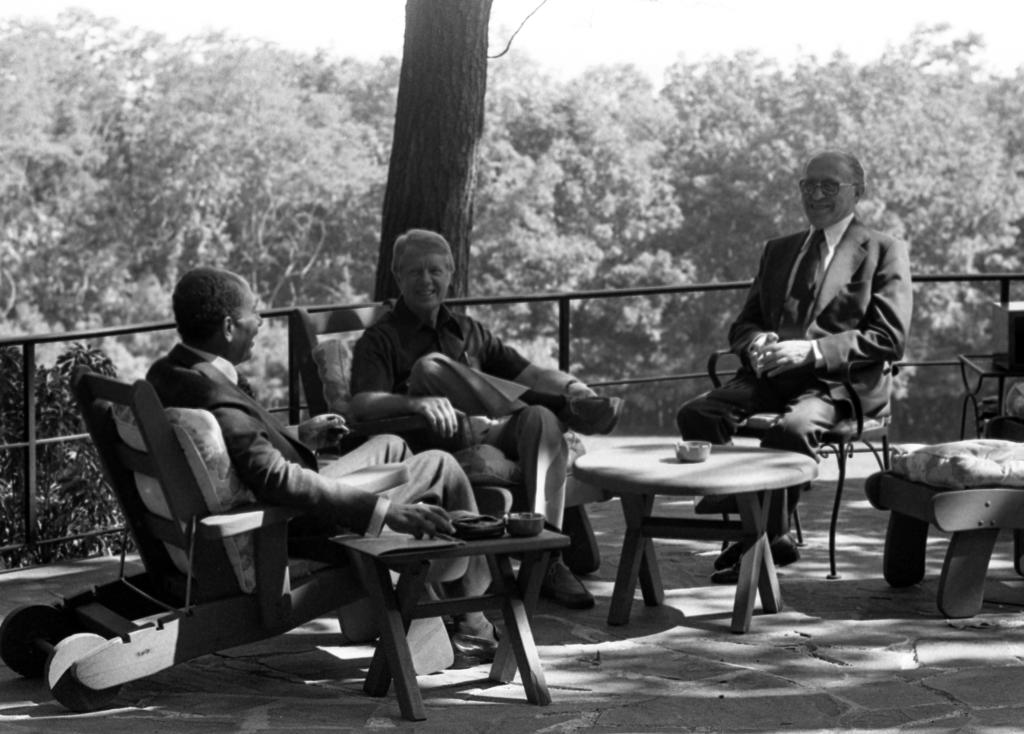

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, U.S. President Jimmy Carter, and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin sit together at Camp David on September 6, 1978.

But despite the best efforts of President Carter and his team, the two men were too incompatible to negotiate at the same table.

For the last ten days and nights of the process, President Carter would go back and forth between the separate cabins where Sadat and Begin were staying, working with his own team, including Hal Saunders, to meticulously craft various documents that they hoped and prayed would serve as the basis for a future peace treaty.

According to Carol Saunders, who married Hal in 1990, the move mirrored the “shuttle diplomacy” in which Hal had participated during the years prior to Camp David.

Nevertheless, by the thirteenth day, the teams had reached an impasse. Neither the spontaneous “shuttle diplomacy” of President Carter and his team, nor the natural beauty of the presidential retreat, had enabled Sadat and Begin to negotiate a peace for their people.

According to Eizenstat, it was Begin who decided to finally call it quits.

There was a plane waiting for him, the prime minister told President Carter. He asked the latter to call him a car. It was to take him away from Camp David—from its natural beauty, from its sense of possibility, and from perhaps the last real chance at Israeli–Egyptian peace in the 20thcentury.

As Begin and his team packed their bags, President Carter had one more, potentially desperate, idea to prevent more Israelis and Egyptians from dying at each other’s hands.

He had to have faith that it would work.

Hal Saunders understood the toll that war had taken on the people of Egypt and Israel.

Throughout both his first career as a U.S. government official and his second as a civilian peacemaker, educator, and founder of the Sustained Dialogue Institute, Saunders paid close attention to the human impact of violent conflict in places like Israel and Palestine, and in regions like the Middle East, South Asia, and the former Soviet Union.

But it was in the midst of his shuttle diplomacy years when the personal dimensions of conflict emerged with painful clarity for Saunders.

In October 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces attacked Israel on Yom Kippur, aiming to reclaim land in the Sinai and the Golan Heights that Israel had occupied in the Six-Day War of 1967.

The 20-day conflict, which came to be known as the Yom Kippur War, or the Ramadan War (as it also fell during the month of Ramadan), claimed the lives of at least 2,700 Israelis, 3,500 Syrians, and 15,000 Egyptians.

In the immediate aftermath, Saunders traveled to Israel as part of his duties as a senior State Department official.

He arrived in a region that was grieving. More than 21,000 families in Israeli, Syria, and Egypt had lost loved ones.

Saunders was grieving, too.

On October 6, the day the Yom Kippur War began, Saunders lost his first wife, Barbara. His children, now without their mother, were nine and seven. Even in his grief, he still committed himself to the ongoing peace process in the Middle East. As he shuttled across oceans and continents, his parents and his late wife’s mother would help create a support network for him and his children.

In a mid-2000s interview with Chris Mitchell, a professor emeritus at the Carter School, Saunders reflected on the impact that period of his life had made on his approach to conflict resolution.

“Almost everybody in Israel knew someone who was killed, missing, or wounded,” Saunders told Mitchell.

When he arrived in Israel following the war and his wife’s death, he met with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir.

“Golda took my hand and said, ‘I’m terribly sorry about your loss. I lost a lot of people, too. I guess we feel somewhat the same,’” Saunders said.

In the following years, that experience of immense personal and collective grief in the midst of political turmoil would continue to resonate for Saunders.

“It was, in a way, an affirmation to me that I needed to maintain my awareness of the human dimensions of the conflict,” he said.

In his work at the State Department, Saunders would strive to address the human impact of violence and war. According to Carol, his determination to not lose sight of the people in the midst of the conflict informed his work as the State Department chargé for the Middle East during the 444 days of the Iranian hostage crisis.

Throughout the crisis, he would gather the spouses of the U.S. hostages together in the State Department for private briefings.

His goal, according to Carol, was to provide the hostages’ loved ones with as much information as he was able so as to allow them to be “as prepared as they could be” when unsettling news was expected in the newspapers.

For Carol, this story exemplified her husband’s character.

“[He was] one of the kindest people I have ever met,” Carol told Carter School News. Calling him a “person of great depth” with regard to his academic and professional knowledge, she said he was also able to plumb the depths of his relationships with those around him.

Saunders’s commitment to seeing the personal in the political was also shared by President Carter, whose own kindness and thoughtfulness—even in the midst of great stress and heavy responsibility—extended to Saunders’s own children.

Sometime after the Camp David summit, before Carter’s presidency ended and their father transitioned from the State Department to a civilian career, Cathy and her brother received a handwritten note from the president, thanking them for contributing to the peace process by being understanding of their father’s work. He appreciated their contributions all the more given the challenges of a single-parent household in the aftermath of their mother’s death.

Before Saunders’s children held that note in their hands, it was another set of notes that would save the Camp David Accords.

September 17, 1978, was a Sunday.

A week before, President Carter, President Sadat, and Prime Minister Begin had been in Gettysburg, where President Carter had hoped “to underscore what [the] wars between Egypt and Israel had meant in lost lives since 1948,” according to Eizenstat.

Now, a week later, Begin was packing his bags, and President Carter and his team had only one more chance to salvage the peace process.

Enter eight photographs.

“Knowing Begin’s love for his eight grandchildren, [President Carter] got each of their names, and he had eight photographs made—copies of himself, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David,” said Eizenstat.

Just as Carter would later write notes to the children of his Assistant Secretary of State, he now “personally inscribed each of the names of [Begin’s] grandchildren” onto the photographs, along with messages expressing his hope that there would one day be peace.

Once he was done, President Carter “walked over to Begin’s cabin, hand delivered [them] to Begin, and watched as he went through and vocalized the names of each of the grandchildren, with blessings for peace by the President,” said Eizenstat.

As Carter observed the prime minister, the latter’s expression began to change.

“Carter saw Begin’s lips quiver, his eyes tear,” Eizenstat said. Then, Begin “put his bags down, and he said, ‘Mr. President, I’ll make one last try.’”

Six months later, in March of 1979, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty that would end three decades of violent conflict between both countries.

The official Camp David Accords, signed on September 17, 1978, by Sadat, Carter, and Begin, would become the foundation for the 1979 peace treaty signed by Egypt and Israel nearly six months later.

For Hal, it was his own personal experiences of both governmental and civilian peace processes, and his observations of the importance of personal relationships to political peace at places like Camp David, that would come to define his calling in peace and conflict resolution.

During his second career, he would go on to write four books, each of them dealing in some way with the impact of personal relationships on prospects for peace.

This deep belief in the power of the personal would also inform his development of the process of Sustained Dialogue. This process is rooted in the conviction that conflict can only be transformed toward peace when relationships between humans—between both individuals and groups—are also transformed.

Books by Hal Saunders

The Other Walls: The Arab-Israeli Peace Process in a Global Perspective (Princeton University Press, 1991)

A Public Peace Process: Sustained Dialogue to Transform Racial and Ethnic Conflicts (Palgrave MacMillan, 2001)

Sustained Dialogue in Conflicts: Transformation and Change (Palgrave MacMillan, 2011)

Politics Is about Relationship: A Blueprint for the Citizens' Century (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014)

When he arrived at George Mason University to teach the next generation of peacemakers, Saunders was eager to share his experiences and insights with his students and colleagues.

According to Cathy, her father—as someone with lived experience in the negotiation of peace—was dedicated to teaching young people more than what could be found in a textbook.

His advice to young people was rooted in his own career path. Cathy observed that though her father held a deep commitment to peace, it was never a foregone conclusion that such a calling would lead to his becoming an assistant secretary in the State Department or a founder of an internationally recognized dialogue institute.

As Saunders navigated his career from undergraduate studies in English at Princeton to the highest levels of the U.S. government, he approached his calling with a mix of curiosity and pragmatism.

“He took the opportunities that seemed right and seemed to fit his talents as they arose,” Cathy said, underlining that his focus on peace helped orient him in a specific direction even without a long-term career goal in mind, though she noted that even as a first-generation college graduate and a factory foreman’s grandson, her father was also helped along by the luck and privilege afforded to many white men in the 1950s.

As much as he could, Saunders was committed to helping his students—and his colleagues in the broader field of peace and conflict resolution—to understand that the work of peacemaking can be done, and needs to be done, at all levels of society.

“For me, a state-centered view of conflict or international relations or domestic politics is just too limiting,” Saunders said in his interview with Mitchell. “Yes, there’s some things only governments can do, such as negotiate peace treaties, but there’s some things that only citizens outside government can do, such as make peace.”

According to Cathy, this firm belief undergirded her father’s approach to educating the next generation of peacebuilders at what is now the Carter School.

“Dad very much believed that everybody contributes to moving the world forward,” Cathy said. “It doesn't need to lead to the White House or Camp David. If it leads to greener practices at the very local level, or to more people voting, or to healthcare, or to just any of those huge number of things we need to work on, all of that is equally important.”

It was a message that Saunders sought to impart to a generation coming of age amidst the turmoil of the new millennium.

In the years after the 9/11 attacks, the memory of those lost ran deep. The subsequent U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan added another dimension to the pain. Just as a cloud of grief had hung over Egypt, Israel, and Syria in 1973, another cloud of grief now hung over thousands of families in the U.S. and across the Middle East and South Asia who had lost their loved ones to the War on Terror.

Perhaps fueled by the tumultuous start to the new millennium, a new generation of students was spurred to learn how to prevent, resolve, and transform conflict.

These students came to the Carter School from across the U.S. and the world. Some were fresh out of their undergraduate studies, while others were experienced professionals looking to advance their first careers or launch their second—or third.

All of them were seeking, in some measure, to do well while doing good.

Unlike those students of the first 15 years of the new millennium, today’s Carter School students don’t have the benefit of learning from Saunders in the classroom.

He passed away in 2016 from prostate cancer.

He would not live to see the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution (known as S-CAR) be named after the last president he served, a renaming that was enabled in part by Saunders’s own relationship with the school and the Carter administration.

But while today’s Carter School students do not have the benefit of knowing Saunders’s depth of kindness and experience firsthand, they do have something else that he left to them: his papers.

According to Carol, “it was Hal's being so impressed by S-CAR, the fact that [the school] really [was] teaching conflict resolution,” that prompted his decision to donate his papers to George Mason University, rather than to his alma maters, Princeton and Yale.

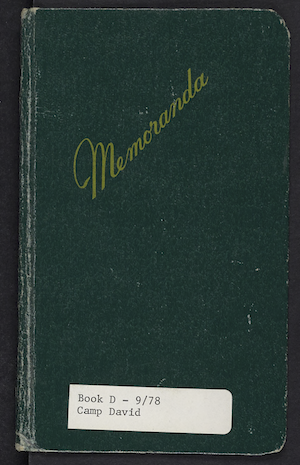

As the couple prepared to move in 2014, Saunders would sit in his chair, sorting through his boxes of notebooks, reports, and photos, meticulously documenting and organizing records of not one but two careers dedicated to building peace.

“That was his life, really, in 60-some cartons,” Carol reflected. “That was what we had poured his heart and soul into.”

When the boxes arrived at George Mason University’s Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), Saunders’s careful attention to the organization of his documents shortened the process of preparing them for digital use by Mason’s faculty and students, as well as the wider public.

Nevertheless, SCRC director Lynn Eaton told Carter School News that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has slowed the process. While most of the collection has been digitized by Backstage Library Works in Pennsylvania, the SCRC team is now undertaking the process of quality control of the PDF documents, which are being optimized for online use, and of the TIFF files, which facilitate “long-term digital preservation.”

Once this phase is complete, then begins the final, arduous, but crucial step of generating metadata for each folder. This will allow the documents to be easily searchable for future researchers and readers from around the world.

The pandemic also means that once the physical collection is back from Pennsylvania, which Eaton estimates will be by the end of October 2020, only faculty, students, and staff at Mason will have access to the documents. Even then, they will be required to make private appointments with the SCRC team so as to maximize physical distancing and follow pandemic-related protocols.

Both Cathy and Carol are hopeful that when the digitization process is complete and the collection is once again able to be viewed safely, Saunders’s papers will serve as an invaluable resource for faculty and students who are deep in the research and practice of conflict resolution.

The collection is organized into three series: 1) documents from Saunders’s government career, 2) documents from his post-government contributions to peacemaking and dialogue, and 3) a collection of notebooks, media, and miscellaneous resources.

For Cathy, it’s her father’s notebooks that stick out in her childhood memory.

Their small size, perfect for carrying to Camp David negotiation tables and church meetings alike, represent “a mix of the mundane and the extraordinary” that she hopes will be a treasure for the Carter School community.

While these materials are being processed, there is another place Carter School community members can go to reflect on Saunders’s contributions to the field of peace and conflict studies: the Point of View International Retreat and Research Center in Lorton, Virginia.

There, students can view photos of Saunders’s participation in U.S. diplomacy and peacemaking efforts and read his multiple books on peace, dialogue, and the centrality of personal relationships to political culture.

Built on land donated by the Lynch family, who are longtime supporters of the Carter School, POV was established to provide both the school and the broader peacebuilding community with a natural space to prompt reflection, dialogue, and peacemaking.

Its views of the waters of Belmont Bay and its quiet paths through the forest have prompted comparisons to Camp David.

The presidential retreat at Camp David “has served as a place of refuge and to bring together world leaders, including to work toward the resolution of intractable conflicts,” said Sheherazade Jafari, who is the director of POV. “Our vision of POV is to serve as a ‘civilian Camp David’—to provide tranquil space and expert support to diverse communities experiencing conflict.”

Pictures of Hal Saunders’s participation in U.S. peacemaking and diplomacy efforts, as well as copies of his books, can be found at the Carter School’s Point of View International Retreat and Research Center in Lorton, Virginia.

While the heart of POV is a state-of-the-art conference facility with meeting and dining rooms, areas for reflection, and a library, its lifeblood is its natural landscape.

The next phase of the retreat’s development will be the building of on-site cottages to “allow visitors to have an even more immersive experience away from distractions as they work through challenges and arrive at solutions together,” according to Jafari.

Even though the residential component is not yet available, Jafari says the school has already seen “how people are transformed after even a few hours of being in the tranquil and beautiful natural setting of the center—from feeling stressed, distracted, and overwhelmed, to feeling calmer and more relaxed, and thus, seemingly more willing to engage with each other creatively and constructively on difficult issues.”

She cautions, however, against viewing the benefits of POV’s natural beauty in isolation of broader peacebuilding questions of equity and justice.

“We need to be looking at how all communities can have access to the benefits that environments like POV offer to our well-being,” she said.

This is especially true as the Carter School community continues to engage with the possibilities of this civilian Camp David, Jafari told Carter School News.

“For example, nature is not always equated with peace for all people,” she said. “[Nature] has also been a place of backbreaking labor with little or no compensation for certain communities, and it is often communities of color who are denied access to safe, natural environments, or whose environments are being destroyed for profit or through the effects of climate change.”

This critical approach to efforts at peacemaking is one that is shared by President Carter himself, not least when he is assessing his own legacy.

For example, while the 1978 Camp David Accords and the resulting 1979 peace treaty between Israel and Egypt has successfully prevented further violent conflict between those two countries, the majority of its goals as relates to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict remain unrealized.

It's a harsh reality that President Carter was not hesitant to underline in his 2006 book.

“Although this crucial peace treaty has never been violated, other equally important provisions of our agreement have not been honored since I left office,” President Carter wrote. “The Israelis have never granted any appreciable autonomy to the Palestinians, and instead of withdrawing their military and political forces, Israeli leaders have tightened their hold on the occupied territories.”

This ongoing conflict continues to impact Palestinian and Israeli communities—including members of the Carter School community, many of whom have lived experience of the conflict and are contributing to efforts to resolve it.

From Jerusalem to DC, Mason alumna dedicates her life to solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

While the Camp David Accords in many ways serve as a reminder to the Carter School’s faculty, students, staff, and alumni of the progress that can be made towards peace and justice, its limitations also remind that the work is neither easy nor without risk.

In 1981, the year that Carter’s presidency ended—and only two years after the 1979 peace treaty was signed—President Sadat was assassinated in an attack by a member of a renegade cell in the Egyptian military. Eleven others would also die in the attack, while twenty-eight people were wounded.

For Carol, the legacies of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, and the fact that the school to which Saunders donated his papers now bears their name, should underline to the school’s community that the work of peace and conflict resolution requires courage, conviction, and an appreciation of the responsibility that comes with seeking to foster peace and justice in one’s own communities and beyond.

After Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter left the White House, “they didn’t just retire to the golf course,” said Carol.

She cited their efforts to continue the work they had started both before and during the presidency, whether by contributing to awareness around mental health, helping to eradicate guinea worm disease and working to eliminate lymphatic filariasis, or volunteering with and supporting Habitat for Humanity.

In this work, Carol said, the Carters have “[given] of themselves, not just their names to put on a plaque.”

“No,” she emphasized. “They rolled up their sleeves.”

In reflecting on the model set by the Carters—and on the model set by Saunders—Carol believes that students at the Carter School can make their own commitment to pursuing peace and justice with responsibility and integrity.

“With the mini Camp David at Point of View, [and] with the naming…[the Carter School has] a responsibility,” she said. “And like any other honor, you must keep that responsibility first and foremost.”

Listen closely enough to be changed by what you hear.

A saying that would guide Hal Saunders in his peacemaking efforts, according to his wife, Carol Saunders. This sentiment can be found inscribed on stones at POV.

The Camp David Accords in Photos

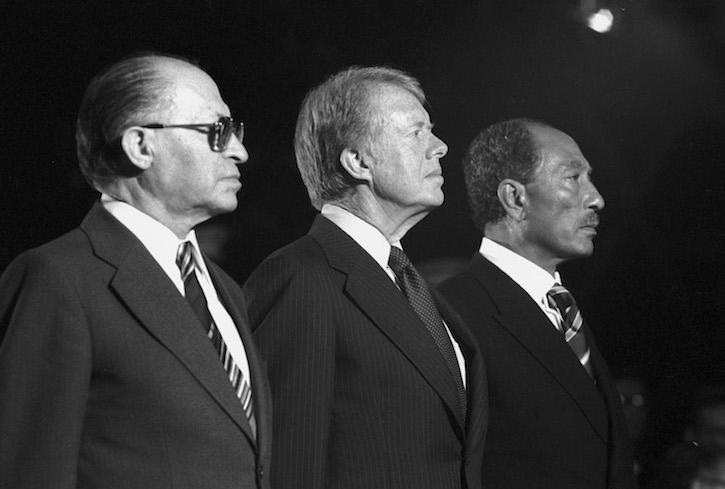

In September of 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter (center) hosted Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin (left) and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (right) at the presidential retreat at Camp David to negotiate one of the most defining peace treaties of the 20th century.

The Camp David Accords were made possible in part by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat's historic visit to Jerusalem in November of 1977, when he became the first leader of an Arab country to address the Israeli Knesset.

Like Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who began his term in 1977, was deeply interested in negotiating peace between Israel and Egypt. However, President Carter noted in his 2006 book, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, that Begin's administration was more hawkish than the previous Israeli administration.

When U.S. President Jimmy Carter entered office in 1977, facilitating peace between Israel and its neighbors was a priority. To bring Israel and Egypt to the table at Camp David would require not only political acumen but also a deep appreciation of the power of personal relationships to make or break prospects for peace.

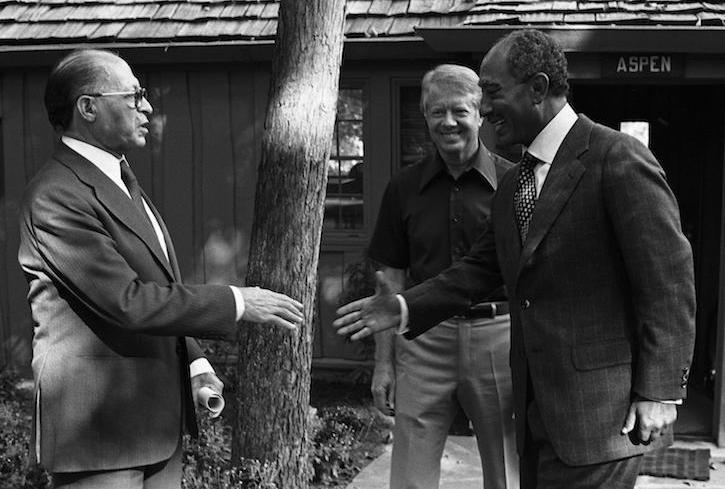

It became clear early in the Camp David negotations that the personalities of Begin and Sadat were incompatible as far as negotiating at the same table was concerned. President Carter and his team decided to separate the delegations to salvage the talks. The "shuttle diplomacy" between the two delegations, as well as personal touches by Carter and his team, resulted in an agreement between the two leaders (pictured here with members of their delegations on September 17, 1978, the final day of the negotiations).

Acknowledgements

The research for and writing of this piece was undertaken in Fall 2020 by Audrey Williams (Carter School Storyteller / News Editor).

The author would like to thank Carol Saunders and Cathy Saunders for sharing their remembrances of Hal Saunders for this story, and for their careful collaboration in spotlighting this narrative of Hal at Camp David. The author would also like to thank Sheherazade Jafari and Justin Ober at Point of View, as well as Lynn Eaton at the Special Collections Research Center, for their contributions to this piece and their work in preserving the record of Hal's scholarship and practice. Finally, the author would like to thank Jeff Zitomer, Director of Marketing and Communications at the Carter School, for his support during the editing stage of this article.