Three of the Carter School's early scholars and practitioners—John W. Burton, James H. Laue, and Wallace Warfield—left an indelible impact on both the school and the field of peace and conflict studies.

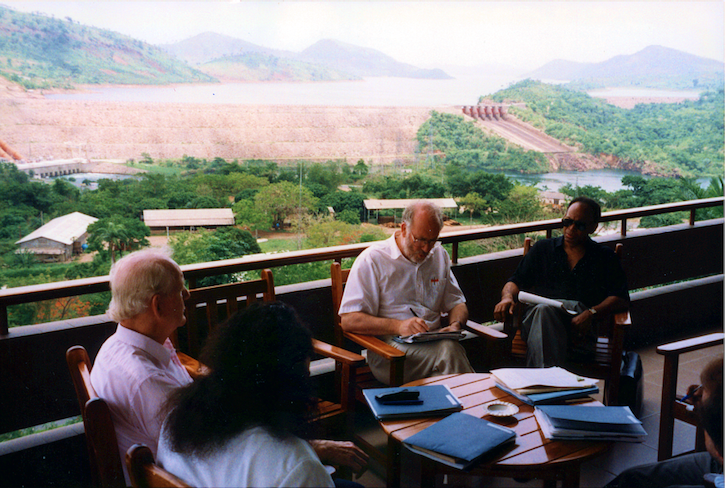

From left – Shireen Kadivar (ICAR PhD student), Amb. John McDonald (then a distinguished visiting professor at ICAR), Chris Mitchell (then ICAR director), and Wallace Warfield (ICAR associate professor) at the Akosombo Dam in Ghana in April 1994. They were participating in a workshop co-organized with the Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy and The Carter Center that brought together representatives of the conflict parties from the First Liberian Civil War.

In 1980, when Bryant Wedge and Henry C. Barringer first approached then George Mason University president George Johnson to propose the creation of the Center for Conflict Resolution, the field of peace and conflict studies was just being born.

In 1981, the newly established center became the first graduate degree-granting program in the field in North America. Nearly forty years later, it is now the largest.

No longer a center, the Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution (formerly the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution) is a place where students from around the world come together to learn from leading scholars in the field. Whether pursuing bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral, or certificate coursework, Carter School students gain access to a multidisciplinary curriculum that places a premium on both research and practice, giving them access to knowledge and skills that will enable them to push the field toward new horizons.

“Students today have a field, and they know that they're coming into a place that is certainly the oldest, the largest, and the most long-lasting place of its kind. Through its faculty [and its] alumni, it has a terrific network of people working in the field. There's a real recognition that faculty and alumni here have helped to write the field into existence. And I think that's an advantage.”

Kevin Avruch (Carter School Dean from 2013 to 2019)

A dedication to rigorous inquiry into the causes of conflict and a serious commitment to innovating sustainable approaches to its resolution have defined the Carter School since its very beginning.

Three of the school's early figures in particular left an indelible mark not only on the field of peace and conflict studies but also on the legacy of the school: John W. Burton, James H. Laue, and Wallace Warfield.

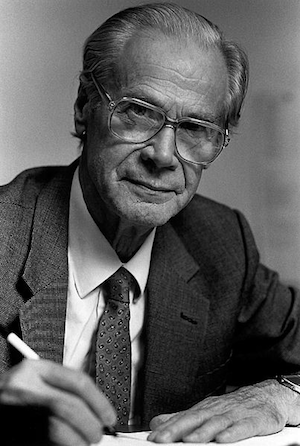

John W. Burton (1915–2010): A Theoretician of the Field

When John W. Burton arrived at the Carter School in 1986, he brought with him a lifetime of engagement in efforts to resolve some of the 20th century’s most pressing conflicts.

Burton began his career in Australia’s diplomatic core. His work took him to the founding conference for the United Nations in 1945 before he became Australia’s youngest ever Head of Foreign Office. As part of the Australian government, he played a role in the decolonization of European overseas empires. When he retired from his career as a diplomat, Burton’s academic career began. His years of service as a diplomat had given him a firsthand look at the tumult of World War II and the early Cold War. He moved to the United Kingdom and launched one of the first conflict resolution centers in Europe, cementing his place as a founding scholar of the peace and conflict studies field.

It was in academia that Burton began to refine his theory that humans have basic needs that are non-negotiable, even in deep-seated conflict situations. Conflicts can arise when these needs are not met, and according to Burton, no resolution to a conflict can be achieved or sustained without considering these needs.

His basic human needs theory would come to be foundational to the nascent field of peace and conflict studies.

Basic Human Needs Theory

In his 1979 book, Deviance, Terrorism & War (Palgrave Macmillan), John W. Burton argued that unless the universal “basic needs of the individual as a social unit” are met—needs for things like recognition, security, and distributive justice—the societies to which those individuals belong cannot hope for indefinite stability.

“[T]he efficient and harmonious functioning of society (as distinct from its integration) is not explained by coercion or by shared values, but by the development and functioning of its component parts, individuals and groups,” Burton wrote. “These requirements are not 'wants' or 'values’; they are needs that are more fundamental than either.”

At the age of 65, Burton retired from academia in the UK and made the jump across the Atlantic to the University of Maryland, where he worked with Edward Azar at the Center for International Development and Conflict.

He met Bryant Wedge just as Mason’s Center for Conflict Resolution was starting out, and Burton began guest lecturing at the center. In 1986, Henry Barringer and Joe Scimecca, the center’s then director, finally convinced Burton to join the program as a distinguished visiting professor.

It was a “watershed moment for the school,” according to a 2017 book on the Carter School's history by Adina Friedman, who received her PhD from the school in 2006 and now serves as an adjunct faculty member.

Burton’s basic human needs theory was the kind of serious and rigorous work that the center was created to foster, support, and disseminate.

“Burton was an enormous presence [at the Carter School],” said current Carter School faculty member Richard Rubenstein, who oversaw the center’s transition to institute status during his tenure as the director from 1989 to 1991. “If there's one person that defined the place, it was him.”

Bringing Burton to the growing center would make a lasting impact on its place in the field.

“He [occupied] a sort of ambiguous position, because he wasn't the director—Joe Scimecca was the director—but he was a very powerful voice in deciding what was going to happen in this place,” said Christopher Mitchell, a professor emeritus at the Carter School who served as its director from 1991 to 1995.

“[He] wanted it to be independent—not to be a government agency; not to be anybody's play thing, you know?” said Rubenstein, who is now the University Professor of Conflict Resolution and Public Affairs at the Carter School. “[He wanted the center] to be able to deal with conflicts even if the United States government was a party, or whoever the parties were.”

At the center, Burton emphasized the centrality of theory to any rigorous effort to address conflict. It would come to define the center’s approach to the study of conflict resolution.

“Burton went on and on about how you couldn't have conflict resolution without analysis, and conflict resolution processes themselves, the good ones, were analytical,” said Rubenstein, who arrived at the center not long after Burton. “So, I said, ‘Well, I guess we should call this place [the Center for] Conflict Analysis and Resolution, not just the Center for Conflict Resolution.’”

With the inclusion of both ‘analysis’ and ‘resolution’ in the name, a linguistic link between theory and practice was established.

The Carter School's Dedication to Theory and Practice

The link between theory and practice, and the dynamic and sometimes fraught discussion around which should take primacy, are defining features of the Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

“One thing that characterized the intellectual understanding [of the school] was that it was never to be a dry, abstract, divorced-from-the-real-world undertaking—that conflict theory and conflict research would always be connected to practice in the world,” said Kevin Avruch, who has been part of the Carter School from its start, beginning as a member of the Faculty Advisory Board before eventually joining the faculty in the school's early years and serving as the dean of the school from 2013 to 2019.

At the Carter School, students receive an in-depth education in the foundational and emerging theories of peace and conflict studies as well as opportunities to put that education to practice in the field through projects guided by Carter School faculty and affiliates.

The result is a student body equipped with a truly multidisciplinary skillset that has prepared them to do the kind of steadfast, rigorous, and reflective work that is required to address multifaceted conflicts in the 21st century.

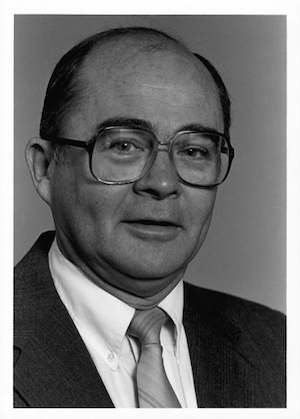

Jim Laue and John Burton at the News Media and Conflict Resolution Conference organized by ICAR in April 1990.

James H. Laue (1937–1993): A Social Change Advocate

According to Kevin Avruch, “if Burton was a kind of intellectual or theoretical voice, the other voice, the other important presence, was a fellow named Jim Laue.”

Born in Wisconsin in 1937, James H. Laue received his PhD from Harvard, where he studied race relations and the sociology of religion. It was the 1960s, and Laue quickly became involved in Civil Rights activism, joining lunch-counter sit-ins and church “kneel-ins.” His activism within the movement, including involvement in protests organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, informed his 1966 dissertation, “Direct Action and Desegregation: Toward a Theory of the Rationalization of Protest.”

As his graduate studies came to a close, he joined the Community Relations Service (CRS) within the U.S. Department of Justice. CRS was established within the framework of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to do the work of preventing and resolving conflicts around race. Laue, an Assistant Director of Community Analysis, was tasked with assessing the potential for racial conflict in communities around the country.

It was this work that had brought Laue to Memphis on April 4, 1968. He was there to contribute to efforts to resolve the Sanitation Workers’ Strike as well as to support the cause of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was in town to support the striking sanitation workers in their “nonviolent struggle for economic justice.” They were both staying in the Lorraine Motel, with Dr. King in Room 306 and Laue in Room 308.

On that day, Laue was in his room when Dr. King was fatally shot standing on the motel’s balcony. Laue was among those, including three of Dr. King’s aides—Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, and Jesse Jackson—who rushed to the side of the Civil Rights Movement leader.

That day, and Laue’s relationship with Dr. King, had a profound impact on the former, one that shaped his work in the field of peace and conflict studies.

“[Dr. King’s] life—and his death—changed my life,” Laue wrote shortly before he passed away in 1993. “He taught me that ‘conflict resolution,’ a laudable goal on the surface, does not truly occur without struggle refined in love and that justice is not fulfilled without reconciliation.”

In 1987, Laue joined the Center for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at Mason as its first Vernon M. and Minnie I. Lynch Chair of Conflict Analysis and Resolution. His presence was instrumental as the center took on the task of seriously incorporating practice into its degree programming.

The Burton–Laue Debates of 1988

From its beginning, the Carter School's multidisciplinary focus and its role in defining the field of peace and conflict studies has made it a center for intellectual curiosity—and intellectual debate.

Rather than shy away from challenging conversations about the possible causes of conflict and the best approaches to its resolution, the Carter School's faculty engage in discussion in both the halls of the school and in the academic literature.

Sometimes, those debates even take place on a more public stage.

In 1988, two of the school's first faculty members, John Burton and Jim Laue, engaged in a series of four conversations of three hours each in front of a gathering of students and faculty, during which they debated the contours and role of neutrality in mediation. Current Carter School faculty member Richard Rubenstein, who was present, reflected on the debate’s implications for social justice in a 1999 article in Peace and Conflict Studies.

“John tended to see serious social conflict as the product of systemic contradictions; only resolution of these contradictions (and reconstruction of failing systems) could resolve deep-rooted conflicts,” Rubenstein wrote in the article. “Jim tended to envision conflict as the product of broken relationships that could be repaired by sensitive mediation and healed by a combination of amity and institutional reform.”

Thirty years later, while reflecting on the debates, Rubenstein told Carter School News that these early disagreements around theory and practice—particularly, around which kinds of theory and practice lead to conflict resolution—helped build a sense of intellectual excitement at the institute.

“You knew you were defining a field,” Rubenstein said. “And then the question was, ‘How should it be defined?’ So, the stakes were pretty high, and people felt that.”

For Laue, years of work as a third-party mediator in communities aching from racial conflict had imbued in him an abiding concern around the ethics of third-party intervention.

“The main thrust of my work while moving back and forth between the roles of activist, academic, commissioner and mediator has been an attempt to develop a discipline of community conflict intervention,” Laue wrote in a 1987 book chapter.

Laue argued that there are five analytically distinct roles an intervenor can play in a conflict: activist, advocate, mediator, researcher, and enforcer. Regardless of the role, however, Laue argued that no intervenor would be able to maintain neutrality in a conflict.

“All intervention alters the power configuration among the parties, thus all conflict intervention is advocacy,” he wrote. “There are no neutrals.”

For Laue, the impossibility of neutrality gave mediators a choice when intervening in a conflict: be an advocate for a certain party, be an advocate for a certain outcome, or be an advocate for “the right kind of process” that will lead to the mutually beneficial resolution of the conflict.

Laue called himself an advocate for the process, but according to Wallace Warfield, his colleague at the institute, Laue was something even more: “You strip away the veneer, you see what he’s really saying. He’s an advocate for social change.”

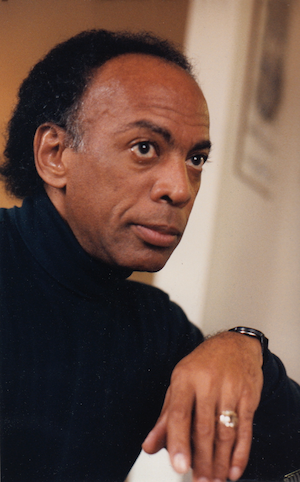

Wallace Warfield (1938–2010): A “Consummate Practitioner”

For Wallace Warfield, to be an effective advocate for social change, especially in the scope of Civil Rights mediation, one was required to keep in mind a vision of a particular type of world.

“You have to have a vision of a just society in order to be able to position yourself,” Warfield reflected during a 2003 interview.

“At key times in that [mediation] process, someone has to say, ‘What kind of world do you want to live in?’” Warfield emphasized. “I think Civil Rights mediation, perhaps more so than other kinds, requires a willingness to be an advocate for a certain kind of society that we live in.”

Before Warfield joined the then Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at Mason, he’d had decades of firsthand experience with working to bring about a more just society in the United States.

Warfield was straight out of college when he began doing work with the New York City Youth Board to prevent and address fighting between gangs. He was doing this work in 1968 when a friend, Jim Norton, encouraged him to consider joining CRS.

Warfield was initially hesitant to take up the offer. He enjoyed his community-level work in New York.

He was facilitating a meeting of parents from the community in New York on April 4, 1968, when he learned of Dr. King’s assassination. “Two months later I was working for the Community Relations Service,” he reflected in the 2003 interview. “It had just changed my life.”

Warfield helped open up the New York regional office for CRS. In 1979, he made the move to the Washington, D.C., office, where he served as an Associate Director of Field Coordination. He then served as the Acting Director of CRS from 1986 to 1988.

During this time, Dennis Sandole, who had joined what was then the Center for Conflict Resolution in 1981 as its first faculty member, invited Warfield to speak to one of his classes at the center. Warfield found that he enjoyed teaching.

In 1990, he began teaching full time, and over the next two decades until his retirement and sudden passing in 2010, he made an immeasurable impact that is still felt at the school.

“At the time we made a great deal of use of practitioners ‘actually doing’ [conflict resolution] in the field and Wallace, the consummate practitioner, was certainly in that category,” wrote Sandole in the foreword to proceedings compiled from an April 2010 Festschrift honoring Warfield upon his retirement.

“He was somebody who knew about conflict—racial conflict. He knew about ethnicity. He knew about conflict in different parts of the States,” Christopher Mitchell reflected in a conversation with Carter School News. “So, he brought something into the institute that supplemented, complemented, Dennis and I, who were sort of interested in what was called ‘international cases.’”

For the program’s students, having access to Warfield’s breadth and depth of knowledge had a profound impact on their learning and doing.

“Several generations of students took from Wallace’s classroom what some considered the transformative experience of their education,” Avruch reflected in a 2013 edited volume of Warfield’s work.

One of those students, Mara Schoeny, earned her MS from the institute in 1997 and her PhD in 2006. Schoeny is now an associate professor at the Carter School, where she also directs the undergraduate program.

“Among his many contributions to the community of practice is mentoring; those of us who have been his students hold this in the highest regard,” Schoeny said during the 2010 Festschrift. “Addition[al] to individual mentoring has been his mentoring of the field, grounded in discussions of ethics and reflective practice. Attention to ethics calls us to pay attention to the motivating as well as aspirational values that inform our analyses and efforts to assist.”

For Warfield, reflective practice was essential to any effort to ethically intervene in conflicts.

According to Schoeny, “reflective practice means finding safe and honest venues for introspection regarding successes as well as failures, outside of a need to explain or promote. For Wallace, reflective practice [was] a vehicle for thinking about how to avoid error in epistemic communities, as well as a way of bringing to light strengths and resources.”

A Theoretician, an Advocate, and a Practitioner

At the Carter School, the legacies of Burton, Laue, and Warfield are encountered in a multidisciplinary curriculum that equips the school’s students with a foundational knowledge of theory meant to inform research and practice that is rigorous, ethical, and reflective.

Just as the school looks back on its founding members and their contributions to the field, it looks forward to the breakthroughs and innovations its students are bringing to peace and conflict studies. Each year, the school awards scholarships honoring the work of Burton, Laue, and Warfield, empowering the next generation of conflict resolvers to make their impact not just on the field, but on the world.

For the students newly arrived at the school with interests and experiences of their own, for the faculty members taking the field in new directions, and for the alumni visiting the school again with stories not just of where they have been and what they have done but also who they now are thanks to their studies at the Carter School, the legacies of Burton, Laue, and Warfield remind not just of where the field has been, but of where it may yet go.

Additional Resources

The following books offer additional information on the intellectual history of the Carter School:

- Adina Friedman, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution: Pioneer in the Field, 1982–2017. Arlington, VA: School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, 2017.

- Alicia Pfund (Ed.), From Conflict Resolution to Social Justice: The Work and Legacy of Wallace Warfield. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Those who are interested in reading work by Burton, Laue, and Warfield are welcome to visit the Burton Library to access the special collection for in-library use. The Burton Library is located at the Carter School in Vernon Smith Hall in Mason Square.

The papers of James H. Laue are accessible within George Mason University's library system.

Acknowledgements

The research for and writing of this piece was undertaken by Audrey Williams (Carter School Storyteller / News Editor), who received her MS in Conflict Analysis and Resolution with a concentration in Media, Narrative, and Discourse in 2020.

The author would like to thank Chris Mitchell, Kevin Avruch, and Rich Rubenstein for sharing their memories of Burton, Laue, and Warfield in interviews during the fall of 2019.